BEHIND THE SEAMS: FASHION AS A WEAPON IN MONSTERS: THE LYLE AND ERIK MENENDEZ STORY

Ryan Murphy’s Netflix series brings killer threads to true crime.

OLIVIA KARLEN

Ryan Murphy’s Netflix drama Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story has seduced true-crime bingers and chronically-online TikTokers alike. The series recounts the tragic tale of Lyle and Erik Menendez, two brothers who infamously killed their parents on August, 20, 1989.

Controversy erupted when Murphy faced backlash for the sensationalist and exploitative nature of the series, with Erik Menendez himself calling it a “dishonest portrayal.” Despite the uproar, I indulged myself in a whirlwind of scandal and obscenity. Armed with popcorn and a taste for salacious television, I sat down for one of the most untamed, gruesomely heartbreaking, and shockingly-hilarious Milli-Vanilli-packed cinematic experiences in my Netflix watch list.

Courtesy of Netflix

I devoured all nine episodes in a single day and the Menendez case quickly became my new hyper-fixation of the month, activating a primal need to know everything about the brothers. My obsession tread into unhealthy territory that turned my TikTok “For You” page into a continuous loop of trial recordings and guilty-pleasure-enabling fan-cams of Nicholas Alexander Chavez.

While I was reeling over the cinematography, jaw-dropping moments, and Nicholas Alexander Chavez’s abs (because let’s be honest, they deserve their own IMDB credit for their phenomenal performance), I was quickly enamored with another visual element: the fashion.

Courtesy of Netflix

Set against a backdrop of quintessential ‘80s style —popped collars on color-blocked windbreakers, sweater vests, teeny tiny shorts, and of course, your Reebok Pumps— this show is a time capsule of sartorial nostalgia. But if you dig a little deeper, the fashion goes beyond the days of Tom Cruise in Cocktail and Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Fashion is a critical part of identity, communication, and ideology. As Veronique Hyland, fashion features director at ELLE, puts it, “identities and associations” are projected onto garments to give them power and authority.

In Monsters, fashion becomes a tool for communication, to shape the identities of the Menendez brothers while manipulating public perception. Let’s break it down.

PRIVILEGED PREP

Lyle and Erik Menendez in the Murphy series sport outfits that ooze wealth and privilege to craft their initially unsympathetic personas. As anthropologist Matthew Joseph Wolf-Meyer notes, clothing acts on ideological and symbolic levels, and reveals the complexities of class systems. Heirs to the fortune of their late father, Jose Menendez, the brothers’ designer wardrobe projects a spoiled, entitled persona onto their identities. Lyle and Erik’s style is 80s bully prep, edging near my-daddy-has-a-boat chic —complete with crisp oxford shirts, khaki shorts, and cashmere sweaters draped nonchalantly over the shoulders like every single trust-fund teen you’ve seen on TV. Pure nepo baby at its finest.

Courtesy of Netflix

Murphy strategically dresses actors Nicholas Alexander Chavez and Cooper Koch in lavish outfits meant to orchestrate entitlement and a lack of sympathy. The characters Lyle and Erik don designer threads and sunglasses inside while yelling at minimum wage workers. In the infamous post-murder shopping spree, the boys flaunt Rolexes and demand luxury items obnoxiously dressed in clothing that amplifies the audience’s preconceived notions of entitlement and reinforces the spoiled privilege that surrounds their identities.

Courtesy of Netflix

CONFINEMENT COUTURE

A transformation in attire once incarcerated reveals a more vulnerable, sympathetic side to Lyle and Erik Menendez. Before their incarceration, their designer outfits served as a flashy mask to hide their true vulnerability and fueled their obnoxious antics. It’s a classic case of “enclothed cognition” —a term coined by psychologists Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky for how clothes influence our psyche and behavior, and commands a powerful shift that exposes their deep-rooted pain. Stripped of their expensive clothes and forced into prison uniforms, the boys finally open up about the horrific abuse they suffered at the hands of their father, Jose Menendez.

The entirety of the fifth episode “The Hurt Man” hones in on Erik who recounts his childhood trauma while dressed in his prison uniform, creating a stark and heartbreaking contrast to the Erik we saw just a few episodes prior. With just a change of clothes, instead of spoiled, cold-blooded killers, we’re watching two young men wrestling with their past.

Courtesy of Netflix

Let’s not forget hair and accessories. Lyle’s wig is a literal and metaphorical mask that signifies his wealth and status. In scenes where it’s removed, we see Lyle stripped bare, revealing his deepest emotions and reminding us that beneath his flashy clothes and groomed hair, lies immense pain.

Courtesy of Netflix

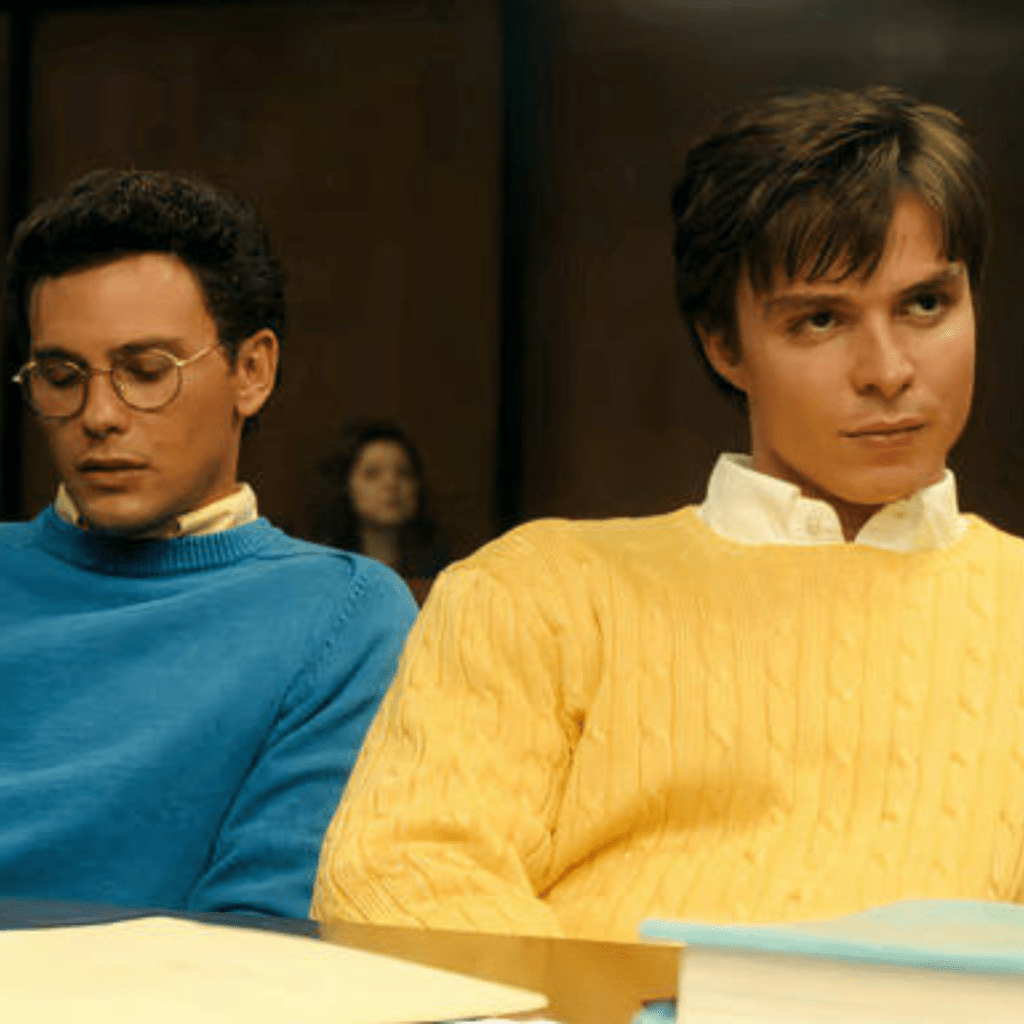

GARB AND GAVEL

Fashion in the Ryan Murphy’s series is a powerful tool that shapes public opinion and is especially evident in the courtroom scenes. Take the Menendez brothers’ first court appearance in the series: they saunter in wearing sharp designer suits, projecting an air privilege to the jurors —think of them as the embodiment of the “wealthy villain” trope. But things take a turn when their defense attorney, Leslie Abrams —a woman of shoulder-padded flair and whirlwind of blond hair— steps in and the Menendez brothers’ look is transformed.

Courtesy of Netflix

Abrams swaps sleek suits for muted pastel sweaters, drab sweater vests over collared shirts, and even non-prescription glasses for Erik. Suddenly, Lyle and Erik resemble lost little boys rather than cold-blooded murderers, evoking a sense of vulnerability that tugs at the jurors’ heartstrings to influence their perceptions. This sartorial manipulation invites the jury to see the brothers as not only reflections of their own children and —while, yes, murderers— victims of their tragic upbringing.

Courtesy of Netflix

THE FABRIC OF IDENTITY

In the realm of television, courtrooms, and even in life, fashion transcends aesthetics. Fashion is a formidable narrative device that not only communicates identity but shapes how we perceive and judge others. In the case of Monsters, the wardrobe choices reveal the intricacies of privilege, trauma, and identity. Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story leaves us to consider the many pieces, sartorial and not, entangled in the concept of identity and how we judge a person to be.